When it comes to dealing with a known safety hazard, everyone is entitled to the same minimum level of protection.

This is the equity argument. It arises from Australia’s work health and safety legislation. It seems elementary. It is elementary. It has also, with the best intentions, been pushed aside by engineers for many years.

The 1974 UK Health and Safety at Work Act introduced the concept of “so far as is reasonably practicable” (SFAIRP) as a qualifier for duties set out in the Act. These duties required employers (and others) to ensure the health, safety and welfare of persons at work.

The SFAIRP principle, as it is now known, drew on the common law test of ‘reasonableness’ used in determining claims of negligence with regard to safety. This test was (and continues to be) developed over a long period of time through case law. In essence, it asks what a reasonable person would have done to address the situation in question.

One key finding elucidating the test is the UK’s Donoghue v. Stevenson (1932), also known as ‘the snail in the bottle’ case, which looked at what ‘proximity’ meant when considering who could be adversely affected by one’s actions.

Another is the UK’s Edwards v. National Coal Board (1949), in which the factors in determining what is ‘reasonably practicable’ were found to include the significance of the risk, and the time, difficulty and expense of potential precautions to address it.

These and other findings form a living, evolving understanding of what should be considered when determining the actions a reasonable person would take with regard to safety. They underpin the implementation of the SFAIRP principle in legislation.

And although in 1986 Australia and the UK formally severed all ties between their respective legislature and judiciary, both the High Court of Australia and Australia’s state and federal parliaments have retained and evolved the concepts of ‘reasonably practicable’ and SFAIRP in our unique context.

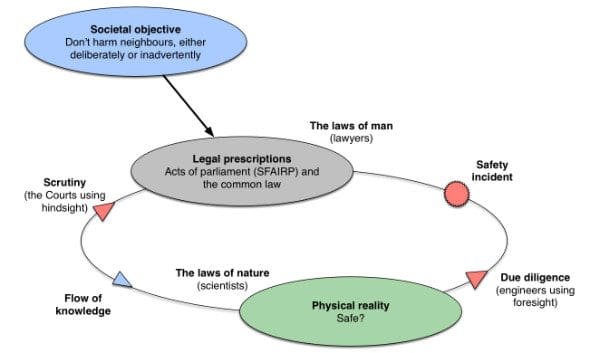

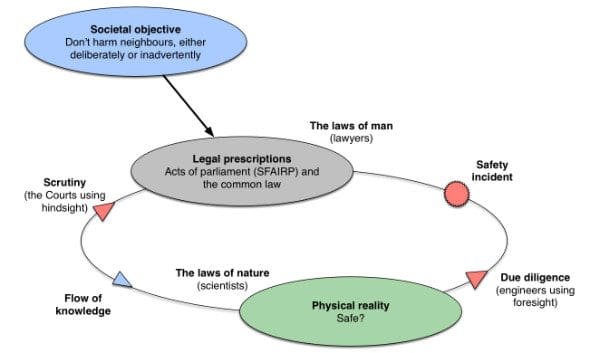

In determining what is ‘reasonable’ the Courts have the benefit of hindsight. The facts are present (though their meaning may be argued). Legislation, on the other hand, looks forward. It sets out what must be done, which if it is not done, will be considered an offence.

Legislating (i.e. laying down rules for the future) with regard to safety is difficult in this respect. The ways in which people can be damaged are essentially infinite. That people should try not to damage each other is universally accepted, but how could a universal moral principle against an infinite set of potential events be addressed in legislation?

Obviously not through prescription of specific safety measures (although this has been attempted in severely constrained contexts, for instance, specific tasks in particular industries). And given the complex and coincident factors involved in many safety incidents, how could responsibility for preventing this damage be assigned?

The most appropriate way to address this in legislation has been found, in different places and at different times, to be to invoke the test of reasonableness. That is, to qualify legislated duties for people to not damage each other with “so far as is reasonably practicable.”

This use of the SFAIRP principle in health and safety legislation, as far as it goes, has been successful. It has provided a clear and objective test, based on a long and evolving history of case law, for the judiciary to determine, after an event, if someone did what they reasonably ought to have done before the event to avoid the subsequent damage suffered by someone else. With the benefit of hindsight the Courts enjoy, this is generally fairly straightforward.

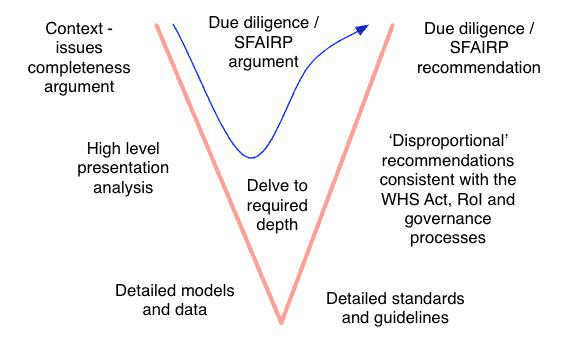

However, determining what is reasonable without this benefit - prior to an event - is more difficult. How should a person determine what is reasonable to address the (essentially infinite) ways in which their actions may damage others? And how could this be demonstrated to a court after an event?

Engineers, as a group, constantly make decisions affecting people’s safety. We do this in design, construction, operation, maintenance, and emergency situations. This significant responsibility is well understood, and safety considerations are paramount in any engineering activity. We want to make sure our engineering activities are safe. We want to make sure nothing goes wrong. And, if it does, we want to be able to explain ourselves. In short, we want to do it right. And if it goes wrong, we want to have an argument as to why we did all that was reasonable.

Some key elements of a defensible argument for reasonableness quickly present themselves. Such an argument should be systematic, not haphazard. It should, as far as possible, be objective. And through these considerations it should demonstrate equity, in that people are not unreasonably exposed to potential damage, or risk.

Engineers, being engineers, looked at these elements and thought: maths.

In 1988 the UK Health and Safety Executive (HSE) were at the forefront of this thinking. In the report of an extensive public inquiry into the proposed construction of the Sizewell B nuclear power plant the inquiry’s author, Sir Frank Layfield, made the recommendation that the HSE, as the UK’s statutory health and safety body, “should formulate and publish guidance on the tolerable levels of individual and social risk to workers and the public from nuclear power stations.”

This was a new approach to demonstrating equity with regards to exposure to risk. The HSE, in their 1988 study The Tolerability of Risk from Nuclear Power Stations, explored the concept. This review looked at what equity of risk exposure meant, how it might be demonstrated, and, critically, how mathematical and approaches could be used for this. It introduced the premise that everyone in (UK) society was constantly exposed to a ‘background’ level of risk which they were, if not comfortable with, at least willing to tolerate. This background risk was the accumulation of many varied sources, such as driving, work activities, house fires, lightning, and so on.

The HSE put forward the view that, firstly, there is a level of risk exposure individuals and society consider intolerable. Secondly, the HSE posited that there is a level of risk exposure that individuals and society consider broadly acceptable. Between these two limits, the HSE suggested that individuals and society would tolerate risk exposure, but would prefer for it to be lowered.

After identifying probabilities of fatality for a range of potential incidents, the HSE suggested boundaries between these ‘intolerable’, ‘tolerable’ and ‘broadly acceptable’ zones, the upper being risk of fatality of one in 10,000, and the lower being risk of fatality of one in 1,000,000.

The process of considering risk exposure and attempting to bring it within the tolerable or broadly acceptable zones was defined as reducing risk “as low as reasonably practicable,” or ALARP. This could be demonstrated through assessments of risk that showed that the numerical probability and/or consequence (i.e. resultant fatalities) of adverse events were lower than one or both of these limits. If these limits were not met, measures should be put in place until they were. And thus reducing risk ALARP would be demonstrated.

The ALARP approach spread quickly, with many new maths- and physics-based techniques being developed to better understand the probabilistic chains of potential events that could lead to different safety impacts. Over the subsequent 25 years, it expanded outside the safety domain.

Standards were developed using the ALARP approach as a basis, notably Australian Standard 4360, the principles of which were eventually brought into the international risk management standard ISO 31000 in 2009. This advocated the use of risk tolerability criteria for qualitative (i.e. non-mathematical, non-quantitative) risk assessments.

And from there, the ALARP approach spread through corporate governance, and became essentially synonymous with risk assessment as a whole, at least in Australia and the UK. It was held up as the best way to demonstrate that, if a safety risk or other undesired event manifested, decisions made prior to the event were reasonable.

But all was not well.

Consider again the characteristics of a defensible argument. It should be systematic, objective and demonstrate equity, in that people are not unreasonably exposed to risk.

Engineers have, by adopting the ALARP approach, attempted to build these arguments using maths, on the premise that, firstly, there are objective acceptable and intolerable levels of risk, as demonstrated by individual and societal behaviour, and, secondly, risk exposure within specific contexts (e.g. a workplace) could be quantified to these criteria. There are problems with mathematical rigour, which introduce subjectivity when quantifying risk in this manner, but on the whole these are seen as a deficit in technique rather than philosophy, and are generally considered solvable given enough time and computing power.

However, there is another way of constructing a defensible argument following the characteristics above.

Rather than focusing on the level of risk, the precautionary approach emphasises the level of protection against risk. For safety risks it does this by looking firstly at what precautions are in place in similar scenarios. These ‘recognised good practice’ precautions are held to be reasonable due to their implementation in existing comparable situations. Good practice may also be identified through industry standards, guidelines, codes of practice and so on.

The precautionary approach then looks at other precautionary options and considers on one hand the significance of the risk against, on the other, the difficulty, expense and utility of conduct required to implement and maintain each option. This is a type of cost-benefit assessment.

In practice, this means that if two parties with different resources face the same risk, they may be justified in implementing different precautions, but only if they have first implemented recognised good practice.

Critically, however, good practice is the ideas represented by these industry practices, standard, guidelines and so on, rather than the specific practices or the standards themselves. For example, implementing an inspection regime at a hazardous facility is unequivocally considered to be good practice. The frequency and level of detail required for inspection will vary depending on the facility and its particular context, but having no inspection regime at all is unacceptable.

The precautionary approach provides a formal, systematic, and objective safety decision-making alternative to the ALARP approach.

Equity with regard to safety can be judged in a number of ways. The ALARP approach considers equity of risk exposure. A second approach, generally used in legislation, addresses equity through eliminating exposure to specific hazards for particular groups of people, without regard to probability of occurrence. For example, dangerous goods transport is prohibited for most major Australian road tunnels regardless of how unlikely they may be to actually cause harm. In this manner, road tunnel users are provided equity in that none of them should be exposed to dangerous goods hazards in these tunnels.

The precautionary approach provides a third course. It examines equity inherent in the protection provided against particular hazards. It provides the three key characteristics in building a defensible argument for reasonableness.

It can be approached systematically, by first demonstrating identification and consideration of recognised good practice, and the decisions made for further options.

It is clearly objective, especially after an event; either the precautions were there or they were not.

And it considers equity in that for a known safety hazard, recognised good practice precautions are the absolute minimum that must be provided to protect all people exposed to the risk. Moving forward without good practice precautions in place is considered unacceptable, and would not provide equity to those exposed to the risk. While further precautions may be justified in particular situations, this will depend on the specific context, magnitude of the risk and the resources available.

Oddly enough, this is how the Courts view the world.

The Courts have trouble understanding the ALARP approach, especially in a safety context. From their point of view, once an issue is in front of them something has already gone wrong. Their role is then to objectively judge if a defendant’s (e.g. an engineer’s) decisions leading up to the event were reasonable.

Risk, in terms of likelihood and consequence, is no longer relevant; after an event the likelihood is certain, and the consequences have occurred. The Courts’ approach, in a very real sense, involves just two questions:

Was it reasonable to think this event could happen (and if not, why not)?Was there anything else reasonable that ought to have been in place that would have prevented these consequences?The ALARP approach is predicated on the objective assessment of risk prior to an event. However, after an event, the calculated probability of risk is very obviously called into question. This is especially so as the Courts tend to see low-likelihood high-consequence events.

If, using the ALARP approach, a safety risk was determined to have less than a one in 1,000,000 (i.e. ‘broadly acceptable’) likelihood of occurring, and then occurred shortly afterwards, serious doubt would be cast on the accuracy of the likelihood assessment.

But, more importantly, the Courts don’t take the level of risk into account in this way. It is simply not relevant to them. If a risk is assessed as ‘tolerable’ or ‘broadly acceptable’ the answer to the Courts’ first question above is obviously ‘yes’. The Courts’ second question then looks not at the level of risk in isolation, but at whether further reasonable precautions were available before the event.

‘Reasonable’ in an Australian legal safety context follows the 1949 UK Edwards v. National Coal Board definition and was refined by the High Court of Australia in Wyong Shire Council v. Shirt (1980). It requires that, when deciding on what to do about a safety risk, one must consider the options available and their reasonableness, not the level of risk in isolation. This is the requirement of the SFAIRP principle.

This firstly requires an understanding of whether options are reasonable by virtue of being recognised good practice. The reasonableness of further options can then be judged by considering the benefit (i.e. risk reduction) they could provide, as well as the costs required to implement them. Options judged as unreasonable on this basis may be rejected. It is only in this calculus that the level of risk (considered first in the ALARP approach) is considered by the Courts.

The ALARP approach does not meet this requirement. If a risk is determined to be ‘broadly acceptable’ then, by definition, risk equity is achieved, and no further precautions are required. But this may not satisfy the Courts’ requirement for equity of minimum protection from risk through recognised good practice precautions. It may also result in further reasonable options being dismissed.

The precautionary approach, on the other hand, specifically addresses the way in which the Courts determine if reasonable steps were taken, in a systematic, objective and equity-based manner. From a societal point of view, the Courts are our conscience. Making safety decisions consistent with how our Courts examine them would seem to be a responsible approach to engineering.

The ALARP approach was a good idea that didn’t work. With the best intentions, it was developed to its logical conclusions and was subsequently found to not meet society’s requirements as set forward by the Courts.

The precautionary approach’s recent prominence has been driven by the adoption of the SFAIRP principle in the National Model Work Health and Safety Act, now adopted in most Australian jurisdictions, followed by similar changes through the Rail Safety National Law, the upcoming Heavy Vehicle National Law and others. And as the common law principle of reasonableness finds it way into more legislation the need for an appropriate safety decision-making approach becomes paramount. It is an old idea made new, and it works. It provides equity.

Is there any good reason to not implement it?

This article first appeared on Sourceable.