Why SFAIRP is not a safety risk assessment

Weaning boards off the term risk assessment is difficult.

Even using the term implies that there must be some minimum level of ‘acceptable safety’.

And in one sense, that’s probably the case once the legal idea of ‘prohibitively dangerous’ is invoked.

But that’s a pathological position to take if the only reason why you’re not going to do something is because if it did happen criminal manslaughter proceedings are a likely prospect.

SFAIRP (so far is as reasonably practicable) is fundamentally a design review. It’s about the process.

The meaning is in the method, the results are only consequences.

In principle, nothing is dangerous if sufficient precautions are in place.

Flying in jet aircraft, when it goes badly, has terrible consequences. But with sufficient precautions, it is fine, even though the potential to go badly is always present. But no one would fly if the go, no-go decision was on the edge of the legal concept of ‘prohibitively dangerous’.

We try to do better than that. In fact, we try to achieve the highest level of safety that is reasonably practicable. This is the SFAIRP position. And designers do it because it has always been the sensible and right thing to do.

The fact that it has also been endorsed by our parliaments to make those who are not immediately involved in the design process, but who receive (financial) rewards from the outcomes, accountable for preventing or failing to let the design process be diligent is not the point.

How do you make sure the highest reasonable level of protection is in place? The answer is you conduct a design review using optimal processes which will provide for optimal outcomes.

For example, functional safety assessment using the principle of reciprocity (Boeing should have told pilots about the MCAS in the 737 MAX) supported by the common law hierarchy of control (elimination, prevention and mitigation). And you transparently demonstrate this to all those who want to know via a safety case in the same way a business case is put to investors.

But the one thing SFAIRP isn’t, is a safety risk assessment. Therein lies the perdition.

Does Safety & Risk Management need to be Complicated?

With Engineer’s Australia recent call-out on socials for "I Am An Engineer" stories, I was discussing career accomplishments with a team member (non-Engineer) and we were struck by how risk and safety need not be complicated – that the business of risk and safety, especially in assessment terms has been over-complicated.

Two such career accomplishments that really brought this home was my due diligence engineering work on:

- Gateway Bridge in Brisbane

Our recommendation was rather than implement a complicated IT information system on the bridge for traffic hazards associated with wind, to install a windsock or flag and let the wind literally show its strength and direction in real time. A simple but effective control that ensures no misinformation. - Victorian Regional Rail Level Crossings

R2A assessed every rail level crossing in the four regional fast rail corridors in Victoria for the requirements to operate faster running trains. The simple conclusion, that I know saved countless lives, was to recommend closing level crossings where possible or provide active crossings (bells and flashing lights) rather than passive level crossings.

However, some risk and safety issues are not as simple, like women’s PPE.

The simple solution, to date, has been for women to wear downsized men’s PPE and workwear. But we know this is not the safest solution because women’s body shapes are completely different to men.

My work with Apto PPE has been about designing workwear from a due diligence engineering perspective. This amounted to the need to design from a clean slate (pattern, should I say!) -- designing for women’s body shapes from the outset and not tweaking men's designs.

Not everyone does this in the workwear sector, but as an engineer, I understand the importance of solving problems effectively and So Far As Is Reasonably Practicable (SFAIRP).

By applying the SFAIRP principle, you are really asking the question, if I was in the same position, how would I expect to be treated and what controls would I expect to be in place, which is usually not a complicated question.

And, maybe, my biggest career accomplishment will be the legacy work with R2A and Apto PPE in making a difference to how people think about and conduct safety and due diligence in society.

Find out more about Apto PPE, head to aptoppe.com.au

To speak with Gaye about due diligence and/or Apto PPE, head to the contact page.

Simplifying Hierarchy of Control for Due Diligence

The hierarchy of control is one of those central ideas that safety regulators have been using forever. But it is also one of those very simple ideas that has caused enormous confusion in due diligence.

In hierarchical control terms, the WHS legislation (or OHS in Victoria) provides for two levels of risk control: elimination so far as is reasonably practicable (SFAIRP), and if this cannot be achieved, minimisation SFAIRP.

In addition, criminal manslaughter provisions have been enacted in many jurisdictions.

The post-event test for this will be the common law test albeit to the statutory beyond reasonable doubt criteria.

For example, from WorkSafe Victoria:

The test is based on the existing common law test for criminal negligence in Victoria, and is an appropriately high standard considering the significant penalties for the new offence.

https://www.worksafe.vic.gov.au/victorias-new-workplace-manslaughter-offences

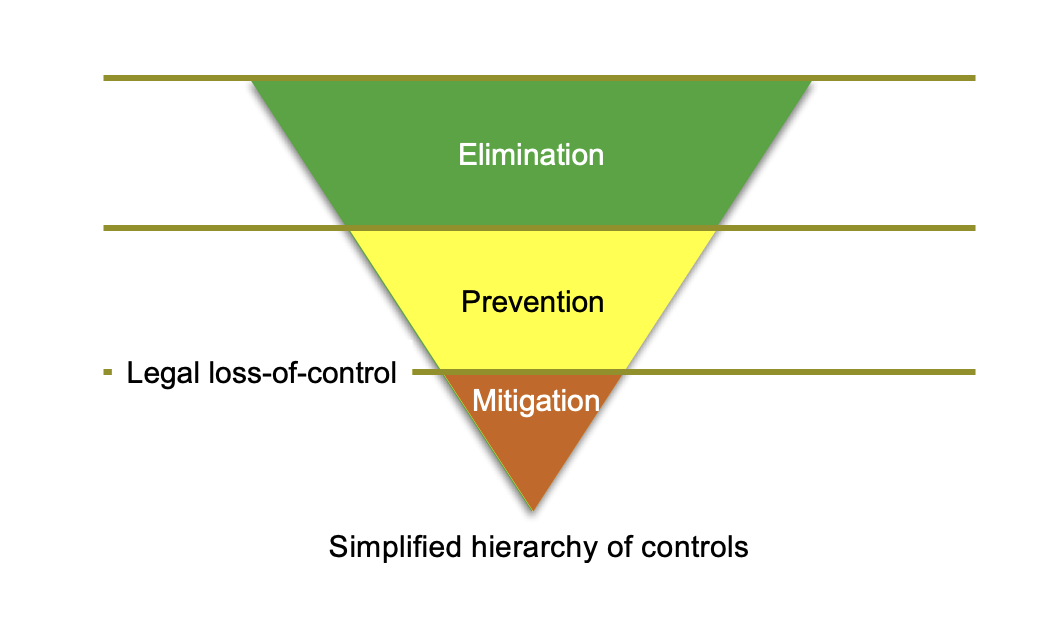

Post-event in court, from R2A’s experience acting as expert witnesses, there are three levels in the hierarchy of control:

- Elimination,

- Prevention, and

- Mitigation.

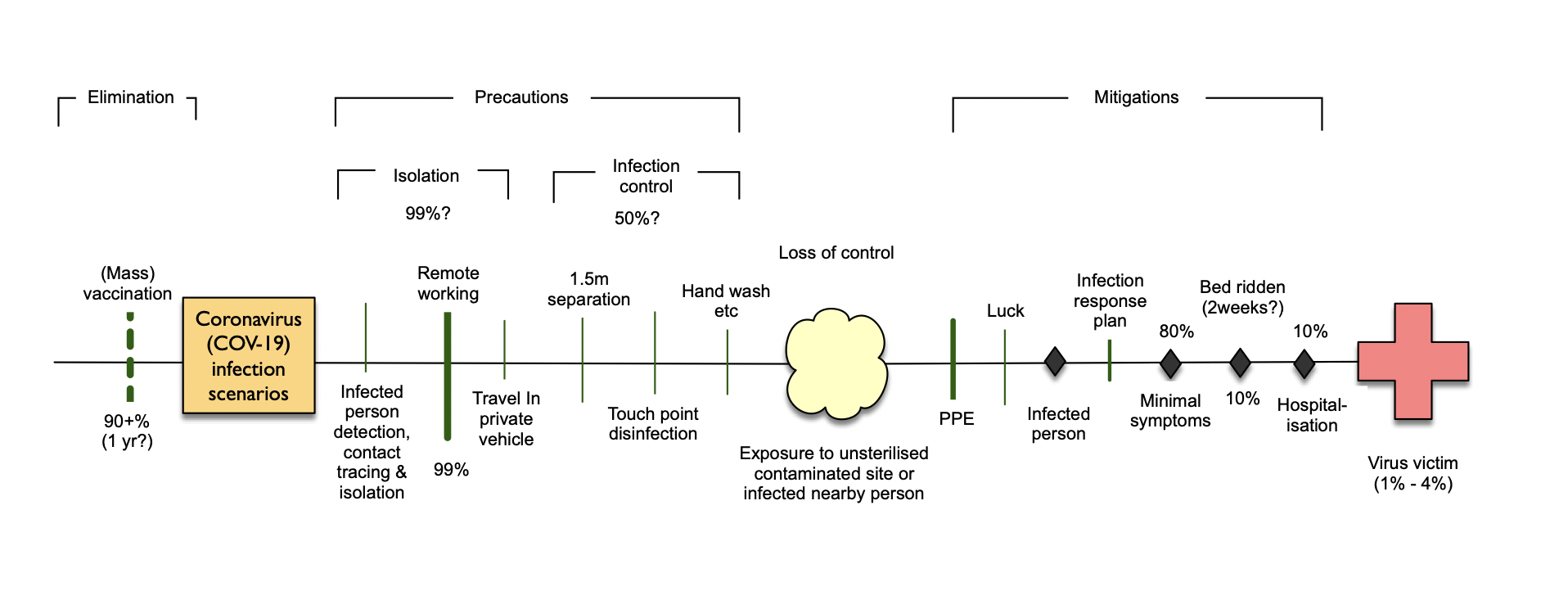

In causation terms most simply shown as single line threat-barrier diagrams such as the one for Covid 19 below.

Our collective safety regulators have other views. For example, the 2015 Code of Practice (How to Manage Work Health and Safety Risks) which has been adopted by ComCare and NSW has 3 levels of control measures whereas many other jurisdictions adopt the 6-level system like Western Australia. Victoria has a 4-level system.

This inconsistency between jurisdictions seriously undermines the whole idea of harmonised safety legislation. And it also muddles optimal SFAIRP control outcomes. For example, engineering can be an elimination option, as in removing a navigation hazard, a preventative control as in machine guarding, or a mitigation as in an airbag in a car.

In R2A’s view, which we have tested with very many lawyers, the judicial formulation shown below is the only hierarchy of control capable of surviving legal scrutiny and R2A’s preferred approach.

Contact the team at R2A Due Diligence for further advice on hierarchy of controls for due diligence.

SFAIRP Culture

The Work Health & Safety (WHS) legislation has changed the way organisations are required to manage safety issues. With the commencement of the legislation in WA on 31 March 2022, as well as the introduction of criminal manslaughter provisions in some states, there appears to be an increased energy around safety due diligence.

The legislation requires SFAIRP (so far as is reasonably practicable).

A duty imposed on a person to ensure health and safety requires the person:

(a) to eliminate risks to health and safety, so far as is reasonably practicable; and

(b) if it is not reasonably practicable to eliminate risks to health and safety, to minimise those risks so far as is reasonably practicable.

This means that the historical concepts of ALARP (as low as reasonably practicable), risk tolerability and risk acceptance do not apply.

From the handbook for the Risk Management Standard (ISO 31000):

Importantly, contemporary WHS legislation does not prescribe an ‘acceptable’ or ‘tolerable’ level of risk—the emphasis is on the effectiveness of controls, not estimated risk levels. It may be useful to estimate a risk level for purposes such as communicating which risks are the most significant or prioritising risks within a risk treatment plan. In any case, care should be taken to avoid targeting risk levels that may prevent further risk minimisation efforts that are reasonably practicable to implement.

(SA/SNZ HB 205:2017 page 14)

In cultural terms, James Reasons outlines three types of risk culture: pathological, bureaucratic and generative.

The SFAIRP approach is attempting to move safety from the pathological question: Is this bad enough that we have to do something about it, to the generative perspective: Here’s a good idea, why wouldn’t we do it?

In this framework, Codes of Practice and Standards are the bureaucratic starting point. The objective is to do better than that, when reasonably practicable to do so. The aim is the highest reasonable level of protection.

The Act ensures a ‘transparent bias’ in favour of safety. As the model act says (and all jurisdictions including NZ have adopted):

… regard must be had to the principle that workers and other persons should be given the highest level of protection against harm to their health, safety and welfare from hazards and risks arising from work as is reasonably practicable.

This is a change in mindset for many organisations, but one which easily aligns with human nature.

On a personal level, we (at R2A) are always trying to do the best we can especially for others. This is one of the reasons I continue to work on Apto PPE, a line of fit-for-purpose female hi vis workwear including a maternity range.

I know that females only represent a small proportion of the engineering and construction section (around 10%), but the question shouldn’t be “is the current options of PPE for women bad enough that we need to do something about it?”

The question should be: Can we do better than scaled down men’s PPE? And Apto PPE is happy to provide an option for organisations that want to do better.