Does Safety & Risk Management need to be Complicated?

With Engineer’s Australia recent call-out on socials for "I Am An Engineer" stories, I was discussing career accomplishments with a team member (non-Engineer) and we were struck by how risk and safety need not be complicated – that the business of risk and safety, especially in assessment terms has been over-complicated.

Two such career accomplishments that really brought this home was my due diligence engineering work on:

- Gateway Bridge in Brisbane

Our recommendation was rather than implement a complicated IT information system on the bridge for traffic hazards associated with wind, to install a windsock or flag and let the wind literally show its strength and direction in real time. A simple but effective control that ensures no misinformation. - Victorian Regional Rail Level Crossings

R2A assessed every rail level crossing in the four regional fast rail corridors in Victoria for the requirements to operate faster running trains. The simple conclusion, that I know saved countless lives, was to recommend closing level crossings where possible or provide active crossings (bells and flashing lights) rather than passive level crossings.

However, some risk and safety issues are not as simple, like women’s PPE.

The simple solution, to date, has been for women to wear downsized men’s PPE and workwear. But we know this is not the safest solution because women’s body shapes are completely different to men.

My work with Apto PPE has been about designing workwear from a due diligence engineering perspective. This amounted to the need to design from a clean slate (pattern, should I say!) -- designing for women’s body shapes from the outset and not tweaking men's designs.

Not everyone does this in the workwear sector, but as an engineer, I understand the importance of solving problems effectively and So Far As Is Reasonably Practicable (SFAIRP).

By applying the SFAIRP principle, you are really asking the question, if I was in the same position, how would I expect to be treated and what controls would I expect to be in place, which is usually not a complicated question.

And, maybe, my biggest career accomplishment will be the legacy work with R2A and Apto PPE in making a difference to how people think about and conduct safety and due diligence in society.

Find out more about Apto PPE, head to aptoppe.com.au

To speak with Gaye about due diligence and/or Apto PPE, head to the contact page.

Simplifying Hierarchy of Control for Due Diligence

The hierarchy of control is one of those central ideas that safety regulators have been using forever. But it is also one of those very simple ideas that has caused enormous confusion in due diligence.

In hierarchical control terms, the WHS legislation (or OHS in Victoria) provides for two levels of risk control: elimination so far as is reasonably practicable (SFAIRP), and if this cannot be achieved, minimisation SFAIRP.

In addition, criminal manslaughter provisions have been enacted in many jurisdictions.

The post-event test for this will be the common law test albeit to the statutory beyond reasonable doubt criteria.

For example, from WorkSafe Victoria:

The test is based on the existing common law test for criminal negligence in Victoria, and is an appropriately high standard considering the significant penalties for the new offence.

https://www.worksafe.vic.gov.au/victorias-new-workplace-manslaughter-offences

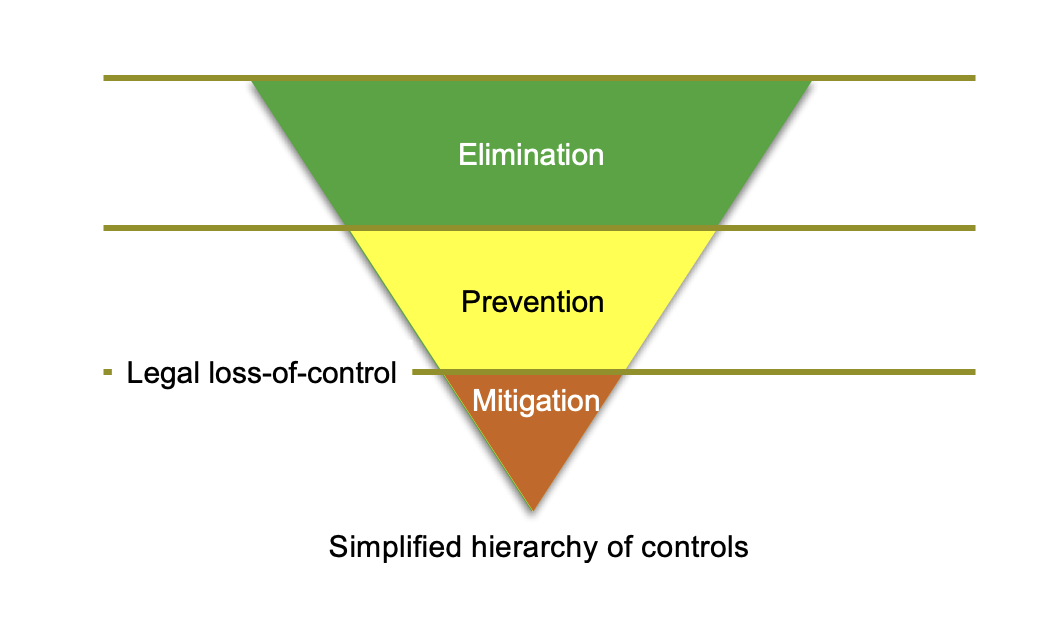

Post-event in court, from R2A’s experience acting as expert witnesses, there are three levels in the hierarchy of control:

- Elimination,

- Prevention, and

- Mitigation.

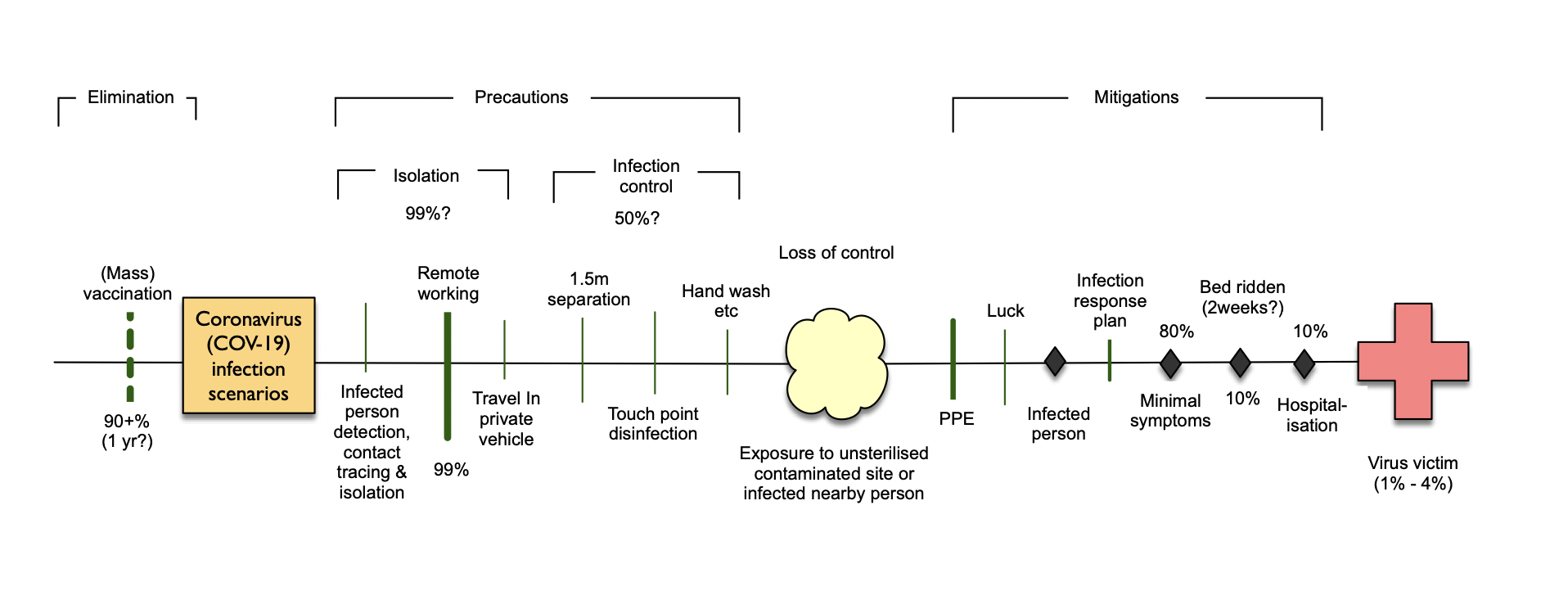

In causation terms most simply shown as single line threat-barrier diagrams such as the one for Covid 19 below.

Our collective safety regulators have other views. For example, the 2015 Code of Practice (How to Manage Work Health and Safety Risks) which has been adopted by ComCare and NSW has 3 levels of control measures whereas many other jurisdictions adopt the 6-level system like Western Australia. Victoria has a 4-level system.

This inconsistency between jurisdictions seriously undermines the whole idea of harmonised safety legislation. And it also muddles optimal SFAIRP control outcomes. For example, engineering can be an elimination option, as in removing a navigation hazard, a preventative control as in machine guarding, or a mitigation as in an airbag in a car.

In R2A’s view, which we have tested with very many lawyers, the judicial formulation shown below is the only hierarchy of control capable of surviving legal scrutiny and R2A’s preferred approach.

Contact the team at R2A Due Diligence for further advice on hierarchy of controls for due diligence.

The Laws of Man vs The Laws of Nature & Safety Due Diligence

One of the odder confusions that R2A happens upon is the proposition that the laws of man are always paramount in all circumstances. It seems to occur most often with persons who work exclusively in the financial sector.

From an engineering perspective, this is just plain wrong.

When dealing with the natural material spacetime universe, the laws of nature are always superior.

After some cogitation, we suspect that this confusion results from the substance of which the financial parties contend, specifically, money.

Sometime ago, over lunch with a banker out of Hong Kong, it was pointed out by R2A that money wasn’t real. The banker expressed surprise and asked what we meant by that. Our reply was that money does not exist in a state of nature. For example, it does not grow on trees. It is a human construct which prosperous societies apparently need to succeed, but of itself, is not directly subject to the laws of nature.

The banker’s response was to ask us not to mention this to anyone.

From this, we conclude that for financial people at least, compliance with legislation and regulations made under it that directly applies to the concept and use of money does demonstrate financial due diligence since the laws of nature are simply not relevant.

However, in the case of safety due diligence, just complying with the laws of man and ignoring the laws of nature will just end in disaster after disaster since the laws of nature are immutable.

To demonstrate safety due diligence requires that the laws of nature are understood and managed in a way that satisfies the laws of man – in that order.

Remember that, legally, safety risk arises because of insufficient, inadequate or failed precautions, not because something is intrinsically hazardous.

For example, flying in a jet aircraft or getting into low earth orbit is intrinsically hazardous, but with enough precautions, it’s fine.

Leave a critical precaution out or let one fail and you will crash and burn. It’s inevitable.

Much the same has been happening with the Covid-19 crisis as discussed in our blog a few months ago (read article here).

Going directly to a political fix without understanding the science is going to hurt. Getting both right is necessary, but it has to be in the right sequence.

Overall, it’s always been no contest – the laws of nature have always trumped the laws of man, except when dealing with non-natural human constructs like money, debt and suchlike over which the laws of nature have no direct control.

Postscript: Risk, as a concept, has many of the same problems as money. It’s a human judgement about what might happen.

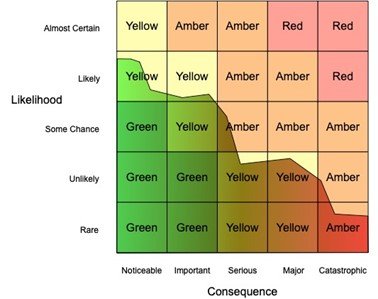

For example, consider the use of the popularly used heat map shown below.

Most users spot-the-dot to characterise the risk associated with a particular issue. But technically it is necessary to know the actual shape of the risk curve for that hazard (the wriggly line going from left to right) which is difficult for real spacetime hazards let alone human judgements of no-material constructs like money.

Strictly it’s also necessary to integrate the area under the risk curve (shown as the darkened area), which is never done. This just goes to show how flexible the concept of risk can be.

Coronavirus Pandemic & Safety Due Diligence

A fabulous array of material has emerged on government websites regarding the Coronavirus (COVID-19). Worksafe Australia has published an interesting article on the connection to WHS legislation. This emphasises that employers have a duty of care to eliminate or minimise risk, so far as is reasonably practicable (SFAIRP).

There then follows numerous precautions described in enormous and voluminous detail. In an attempt to cut to the chase, R2A decided to apply our usual precautionary approach to the whole thing to see if we clarify what all this means.

So far as we can tell, the core difficulty with the new coronavirus is that it is very, very contagious. Much more so than ordinary flu.

This means it will escalate with startling speed and easily overwhelm our medical resources unless stringent measures to reduce the infection rate are implemented.

To calculate the infection rate, a probabilistic epidemiological model appears to be being used, conceptually shown above. That is, all the individual transmission pathways may not be fully understood, but an overall probabilistic transmissivity model can be created.

From a statistical viewpoint, if enough people are involved, the predictions should be quite robust and is presumably the basis of our governments’ concerns.

Causal workplace infection pathway single line threat barrier diagram

Following the hierarchy of controls, the threat-barrier diagram above identifies the elimination option (a vaccine), the precautions such as isolation and infection control prior to the loss of control point and then the mitigation options including hospitalisation which act after the loss of control point.

However, from the perspective of any single infection, there will likely be a single causal chain of events, which can be interrupted in various ways, particularly following the hierarchy of controls enshrined in the WHS legislation.

Such an understanding enables SFAIRP to be demonstrated. There would be different sequences for different paths; family, hospitals, workplace, team sports and the like.

From an employer /employee perspective, we think the single line threat-barrier diagram shown above is a reasonable first cut.

If you'd like to learn more about our Safety Due Diligence approach, read our White Paper here.

Why your team has a duty of care to show they've been duly diligent

In October and November (2018), I presented due diligence concepts at four conferences: The Chemeca Conference in Queenstown, the ISPO (International Standard for maritime Pilot Organizations) conference in Brisbane, the Australian Airports Association conference in Brisbane (with Phil Shaw of Avisure) and the NZ Maritime Pilots conference in Wellington.

The last had the greatest representation of overseas presenters. In particular, Antonio Di Lieto, a senior instructor at CSMART, Carnival Corporation's Cruise ship simulation centre in the Netherlands. He mentioned that:

a recent judgment in Italian courts had reinforced the paramountcy of the due diligence approach but in this instance within the civil law, inquisitorial legal system.

This is something of a surprise. R2A has previously attempted to test ‘due diligence’ in the European civil (inquisitorial) legal system over a long period by presenting papers at various conferences in Europe. The result was usually silence or some comment about the English common law peculiarities.

The aftermath of the accident at the port of Genoa. Credit: PA

The incident in question occurred on May 2013. While executing the manoeuvre to exit the port of Genoa, the engine of the cargo ship “Jolly Nero” went dead. The big ship smashed into the Control Tower, destroying it, and causing the death of nine people and injuring four.

So far the ship’s master, first officer and chief engineer have all received substantial jail terms, as has the Genoa port pilot. It seems that a failure to demonstrate due diligence secured these convictions

And there are two more ongoing inquiries:

- One regards the construction of the Tower in that particular location, an investigation that has already produced two indictments; and

- The second that focuses on certain naval inspectors that certified ship.

It's important to realise everyone involved -- the bridge crew, the ship’s engineer, ship certifier, marine pilot, and the port designer -- all have a duty of care that requires, post event, they had been duly diligent.

Are you confident in your team's diligent decision making? If not, R2A can help; contact us to discuss how.

2017: The Year in Review

It’s hard to believe that 2017 is coming to a close and 2018 is almost here. As part of our end of year wrap up, here are some of the highlights that we would like to share with you.

In February R2A together with the Victorian Bar had the pleasure of presenting Cambridge Reader in Law and former British MP, Professor David Howarth for a special session, co-chaired by the Victorian Bar and Engineers Australia, exploring his latest book, Law as Engineering.

Professor Howarth’s essential point in his book is that these days most lawyers don’t litigate. Rather, they design social constructs such as contracts, companies, treaties and wills to facilitate their clients’ wishes. This is similar to how engineers design physical constructs to satisfy their clients’ desires.

David’s event sparked useful and interesting discussions between the engineering and legal professions.

Gaye's role on the Powerline Bushfire Safety Committee continued this year. Gaye’s role is to provide risk management and best practice advice.

We were privileged to work with many clients throughout the year. Here are a few of the interesting projects completed during the year.

INTERESTING PROJECTS

Bicycle Access Management Review. Earlier this year R2A assisted Queensland’s Department of Transport and Main Roads (TMR) with the development, testing and implementation of a risk assessment methodology for bicycle access management. Following a series of information-gathering tasks, R2A developed a proposed SFAIRP[1] decision-making process for bicycle access management on state-controlled roads. TMR is currently preparing a supporting policy for state-wide implementation.

Asset Risk Management Framework Review. R2A completed a review to develop an asset safety risk management framework consistent with the requirements of the Work Health and Safety Act (WHS) 2012, the TasNetworks Risk Management Framework (2015) and the TasNetworks Asset Management Plan (2015) whilst simultaneously taking into account the requirements of Tasmania’s electricity safety regulator (the Department of Justice) and the national electricity economic regulator (the AER).

Gold Coast Desalination Plant Access Review. R2A undertook a commission to conduct a safety due diligence review of the Gold Coast Desalination Plant access arrangements to the high-pressure areas whilst the plant is producing water.

State Emergency Risk Assessment Review. This project was undertaken to confirm the appropriateness of the State’s priority emergency risks, the controls in place and their effectiveness as well as and if required revise the risk characterisation in line with the updated National Emergency Risk Assessment Guidelines (NERAG) 2014.

Rail Project Business Case Reviews. R2A completed a number of business case reviews were this year for PTV and Trasport for Victoria, including the Safer Country Crossings and DDA Access Improvements Programs.

Plant and Equipment Review. R2A were engaged by DEDJTR to review its plant and equipment safety management systems at 8 key Department research farms. This provided a basis for a larger Department program to enhance its safe and efficient management of physical assets.

Fire Loss Risk Methodology Review. The purpose of R2A’s review was to ‘test’ the proposed methodology and to provide advice as to its effectiveness or otherwise of demonstrating ‘as far as practicable’ in the management of bushfire risk, particularly with regard to the question of disproportionality.

The Grimes Review

On 19 January 2017, the Minister for Energy, Environment and Climate Change announced an independent review of Victoria’s Electricity Network Safety Framework, to be chaired by Dr Paul Grimes. On 5 May 2017, the Minister announced an expansion to the Review’s Terms of Reference to include Victoria’s gas network safety framework. R2A provided submissions for both gas and electrical safety, and met with Dr Grimes twice.

Pleasingly, from R2A’s perspective, the recommendation in the interim report stated that the decision-making criteria for safety should be consistent with that of the 2004 OHS act, that is, a precautionary approach that uses the SFAIRP principle rather than an ALARP principle using target levels of risk.

In coming to this view Dr Grimes comments favourably on the R2A understanding of issues involved.

The final report is expected to be released early next year.

CONFERENCES

Earlier this year Tim presented at the Fire Australia Conference in Sydney on The Legal Context to QRA. Whilst Gaye presented her paper on How safe is safe enough? Effective Safety Frameworks at EECon in Melbourne. Richard also presented to two groups of marine pilots on pilotage safety due diligence at SmartShip.

We have availability for similar opportunities next year. Drop us a line if you have an event coming up.

MEDIA

Richard and Tim continued to write for Sourceable this year:

- Engineering’s Golden Rule (March 2017)

- Design Safety Decisions Don’t Disappear (May 2017)

- Scientific Management and the AER (July 2017)

- Regulators Put Cost Before Safety (August 2017)

- Explaining Engineering Judgement (November 2017)

EDUCATION

From an education perspective, Richard delivered numerous public and in-house courses on Engineering Due Diligence as well as continuing to deliver the Swinburne post-graduate unit Introduction to Risk & Due Diligence with Gaye and Tim both presenting guest lectures.

The 2-day joint R2A/EEA engineering due diligence workshop was again successful this year and will continue in 2018. This workshop is aimed at aspiring directors and senior managers.

[1] “So far as is reasonably practicable”, as required by the 2011 Work Health and Safety Act.

Should you attend the Engineering Due Diligence Workshop?

An introduction to the concept of Engineering Due Diligence

Engineering is the business of changing things, ostensibly for the better. The change aspect is not contentious. Who decides what’s ‘better’ is the primary source of mischief.

In a free society, this responsibility is morally and primarily placed on the individual, subject always to the caveat that you shouldn’t damage your neighbours in the process. Otherwise you can pursue personal happiness to your heart’s content even though this often does not make you as happy as you’d hoped. And it becomes rapidly more complex once collective cooperation via immortal legal entities known as corporations came to the fore as the best way to generate and sustain wealth. This is particularly significant for engineers as the successful implementation of big ideas requires large scale cooperative effort to the possible detriment of other collectives.

The rule of law underpins the whole social system. It is the method by which harm to others is minimised consistent with the principle of reciprocity (the golden rule – do unto others as you would have done unto you) prevalent in successful, prosperous societies. In Australia it has been implemented via the common law and increasingly, in statute law. Company directors, for example, have to be confident that debts can be paid when they fall due (corporations law), workers (and others) should not be put unreasonably at risk in the search for profits (WHS law) and the whole community should be protected against catastrophic environmental harm (environmental legislation). It is unacceptable for drink-drivers to kill and injure others, the vulnerable to be exploited or the powerful to be immune from prosecution. Everyone is to be equal before the law.

Provided such outcomes are achieved, the corporation and the individuals within them are pretty much free to do as they please. Monitoring all these constraints and ensuring the balance between individual freedoms and unreasonable harm (safety, environmental and financial) to others has become the primary focus of our legal system.

But the world is a complex place and its difficult to be aways right particularly when dealing with major projects. But it is entirely proper to try to be right within the limits of human skill and ingenuity. The legal solution to address all this has been via the notion of ‘due diligence’ and the ‘reasonable person’ test.

Analysing complex issues in a way that is transparent to an entire organisation, the larger society and, if necessary, the courts can be perplexing. Challenges arise in organisations when there are competing ideas of better, meaning different courses of action all constrained with finite resources. This EDD workshop provides a framework for the various internal and external stakeholders to listen to, understand and decide on the optimal course of action taking into account safety, environmental, operational, financial and other factors.

To be ‘safe’, for example, requires that the laws of nature be effectively managed, but done in a way that satisfies the laws of man, in that order.

Engineering Due Diligence Workshop

The learning method at the R2A & EEA public workshops follows a form of the Socratic ‘dialogue’. Typical risk issues and the reasons for their manifestation are articulated and exemplar solutions presented for consideration. The resulting discussion is found to be the best part for participants as they consider how such approaches might be used in their own organisation or project/s.

Current risk issues of concern and exemplar solutions include:

- Project schedule and cost overruns. This is much to do with the over-reliance on Monte Carlo simulations and the Risk Management Standard which logically and necessarily overlook potential project show-stoppers. A proven solution using military intelligence techniques will be articulated. This has never failed in 20 years with projects up to $2.5b.

- Inconsistencies between the Risk Management Standard and due diligence requirements in legislation, particularly the model WHS Act. A tested solution that integrates the two is presented, as is now being implemented by many major Australian and New Zealand organisations, shown diagrammatically below.

- Compliance does not equal due diligence. Solutions are provided to avoid over reliance on legal compliance as an attempt to demonstrate due diligence. It also demonstrates how a due diligence approach facilitates innovation.

- The SFAIRP v ALARP debate. Model solutions presented (if relevant to participants) including marine and air pilotage, seaport and airport design (airspace and public safety zones), power distribution, roads, rail, tunnels and water supply.

Participants are also encouraged to raise issues of concern. To enable open discussion and explore possible solutions, the Chatham House Rule applies to participants’ remarks meaning everyone is free to use the information received without revealing the identity or affiliation of the speaker.

To find out more information about the Engineering Due Diligence Workshop held in partnership with Engineering Education Australia, head to our workshop page or contact course facilitator, presenter and R2A Partner Richard Robinson at richard.robinson(@)r2a.com.au or call 1300 772 333.

If you're ready to register, do so direct via EEA website here.

Engineering: Ideas and Reality

Engineers play an integral role in bringing society’s wishes to fruition. As Engineers Australia’s monthly magazine create notes, we engineer ideas into reality.

However, when we go about taking ideas and making them real we have responsibilities. We are obliged to consider the ideas’ risks as well as benefits. We must ensure that our engineering activities meet our society’s expectations, and in particular that we address all our legal duties as engineers.

And so, even as we engineer new ideas into reality, we must also engineer the new reality we create into ideas – the ideas expressed in Australia’s laws.

Australia is an egalitarian society. Our judicial and political systems are predicted on the basis of equality for all before the law. This gives rise to a number of interesting ideals. For instance, one of our fundamental legal safety principles is that, for a known safety hazard, everyone is entitled to the same minimum level of protection. This arises from work health and safety legislation in all states and territories.

As another example of this, recognised good practice is a standard to which all engineers are held, in safety matters and otherwise. Engineering good practice is demonstrated in many ways, including standards and guidelines for design, operation, asset management and so on. It is also presented in regulations, which essentially present good practice that is so well recognised that the governments agree that it must be mandated. The National Construction Code is a prime example of this.

This reliance on recognised good practice means that, for instance, an engineering project manager who fails to implement recognised good practice measures to address the risk of project cost or timeline overrun would very likely expose his organisation to civil liabilities.

The simplest, cheapest and most effective way for engineers to address these and other legal requirements is to adopt systems and processes that demonstrate due diligence, that is, that all reasonable measures have been taken. This approach ensures engineering activities and engineering decisions are conducted in a manner consistent with legal requirements – that as we engineer ideas into reality, we also engineer reality to the right ideas.

To learn more about demonstrating due diligence as engineers, register for EEA’s Engineering Due Diligence workshop.

Scientific Management and the AER

Scientific management appeared as a formalised concept in 1910. In its idealised form it involved observing workers performing tasks, identifying potential efficiencies that could be gained in time or effort, and implementing changes.This was followed, of course, by scientific management consultants invoicing businesses for these services.This approach (including the invoicing) seems to have been first implemented by Frederick Winslow Taylor, an industrial engineer from Philadelphia. It was named in 1910 and subsequently popularised by Louis Brandeis, a Boston lawyer later made an Associate Justice of the US Supreme Court, Frank Gilbreth, a building contractor and superintendent, and his wife Lillian, who had a background (and eventually a doctorate) in psychology.Taylor, Brandeis and the Gilbreths differed in their motivation and focus in this emerging field. Taylor had as his tool a stopwatch, focusing on potential time savings in tasks, often through greater exertion on behalf of manual labourers. The Gilbreths used a movie camera to study workers, classifying 17 ‘elementary’ units of movement they named ‘therbligs’ and identifying wasted time and motion.Brandeis, on the other hand, did not practice scientific management himself. In his work as a lawyer, he came across the concepts of scientific management. He used these to successfully argue (among other things) that the basis of freight prices set by rail carriers were arbitrary and excessive, and that scientific management could demonstrate great potential gains in efficiency, and hence that carriers ought not to raise their prices.Brandeis used consultants to identify these efficiencies through Taylor's and the Gilbreths' methods, with the aim of reducing the effort and complexity required for specific tasks. Through this, he came to believe that the ideas espoused by Taylor and the Gilbreths could be used to reduce costs, raise wages (especially for low-paid workers), and generally enhance workers’ standard of living.Brandeis attempted to bring this approach to labour disputes, campaigning to unions on the benefits of scientific management. Unions, however, were skeptical, seeing (not without justification) a slippery slope to the commodification of workers as indistinguishable parametric units, rather than individual human partners in enterprise.Regardless, the concept of scientific management spread quickly, resulting directly and indirectly in a wide range of today’s approaches to business and efficiency, including strategic management, large parts of MBA courses, human factors, and widespread organisational benchmarking.Benchmarking is used in a wide range of contexts, including quantity estimation, business planning and management, industry regulation, and many others. It provides insight into expectations of time and cost, and helps identify outliers that may warrant further attention.In view of the ‘natural’ monopoly nature of Australian electricity distribution networks, electricity network businesses are subject to economic regulation by the federal Australian Energy Regulator (AER) and safety regulation by state-based agencies, such as IPART in NSW, and Energy Safe Victoria (ESV). These regulators essentially attempt to balance the networks’ business interests against the interests of the community, both financial (such as reasonable electricity prices) and safety (such as the networks’ bushfire management actions).The AER promotes this community financial interest through its authority to (attempt to) replicate the commercially beneficial effects of a ‘market’. One mechanism used in this process is limiting the prices distribution networks can charge for electricity supply. Similar to Brandeis’ assessment of freight prices set by rail carriers, these limits are in partly based on the expected (benchmarked) cost of time, materials and labour for particular tasks.There is no doubt that as electricity networks have been privatised, the AER’s approach has resulted in the maintained affordability of electricity, an essential service, to the Australian community. However, the separation of the financial and safety regulatory functions has resulted in some unintended consequences.The AER’s determination of distribution networks electricity supply prices includes consideration of expected asset maintenance and replacement. This translates through the distribution networks' operations to their field work scheduling. Field workers are allocated a certain number of asset tasks to be completed in a certain time frame. However even with an allowance for some of the expected work, this drives the perceived responsibility of any shortfall of tasks or exceedance of timeframe to the field worker.The practical result is that electrical workers in the field are driven to act on a benchmarked price/time unit rate and to ignore incipient safety issues, especially to third parties the public) that should otherwise be reported and dealt with, in efficient economic terms, on the spot. In the hierarchy of day-to-day concerns, workers may become more focused on failing to complete each day’s scoped tasks than dealing with safety issues that arise. In terms of James Reason’s theory of risk culture, it encourages distribution networks in safety terms to move from generative to pathological. That is, workers are disincentivised from bringing safety problems to management’s attention.This is a spectre of the issue the unions raised to Brandeis when he assured them that scientific management would increase their members’ lots in life. Great benefit may be gained from the quantification and benchmarking of organisations. But this must be done in the context of the people carrying out the tasks. If it is not, workplace culture (safety and otherwise) is corroded, and workers’ perception being that management views them simply as numbers or automatons, rather than people, leads to a self-fulfilling prophecy.

This article first appeared on Sourceable.

Engineering Due Diligence Workshop

The learning method at the R2A-EEA public workshops follows a form of the Socratic ‘dialogue’. Typical risk issues and the reasons for their manifestation are articulated and exemplar solutions presented for consideration. The resulting discussion is found to be the best part for participants as they consider how such approaches might be used in their own organisation or projects.

Current risk issues of concern and exemplar solutions include:

- Project schedule and cost overruns. This is much to do with the over-reliance on Monte Carlo simulations and the Risk Management Standard which logically and necessarily overlook potential project show-stoppers. A proven solution using military intelligence techniques will be provided. This has never failed in 20 years with projects up to $2.5b.

- Inconsistencies between the Risk Management Standard and due diligence requirements in legislation, particularly the model WHS Act. A tested solution that integrates the two is presented, as is now being implemented by many major Australian and New Zealand organisations.

- Compliance ≠ due diligence. Solutions to avoid over reliance on legal compliance as an attempt to demonstrate due diligence are provided.

- SFAIRP v ALARP debate. Model solutions presented (if relevant to participants) including marine and air pilotage, seaport and airport design (airspace and public safety zones), power distribution, roads, rail, tunnels and water supply.

Participants are also encouraged to raise issues of concern. To enable open discussion and explore possible solutions, the Chatham House Rule applies to participants’ remarks meaning everyone is free to use the information received without revealing the identity or affiliation of the speaker.

Remaining dates for 2017 are:

Perth 21 & 22 JuneBrisbane 23 & 24 AugustWellington 5 & 6 SeptemberMelbourne 25 & 26 October

Legal vs Engineered Due Diligence

The rise of the model Work Health and Safety legislation, and the need for officers to demonstrate due diligence to ensure that their business has all reasonable practicable safety precautions in place, has been interpreted in different ways.It’s not just a cynical exercise to cover your arse after the event (although that will be one outcome).When conducting investigations into industrial fatalities, the deceased’s co-workers often self-assess to see if there is something that they personally could have done that might have saved their mate. If there was, they feel really, really bad. Conversely, if after due consideration, they conclude that they had done everything in their power to prevent such an occurrence, they feel relieved.This is the natural human response. You can also see this occur with response of parent to the death of a child on ‘P’ plates. The parents always think long and hard about whether they should have done more to train their daughter or son before they were allowed unsupervised on the roads. The Bushfire Royal Commission into the 173 deaths arising from the Black Saturday fire is a similar response, but at a community level.The courts also serve this function, but at a societal level and in a very formal context. When considering cases dealing with health and safety impacts they ask, in effect, “Was there something else that ought to have been done that would have prevented this outcome?”This is our society’s introspection, which helps us feel that justice is served, and that we learn from our mistakes.Accepting this, how do we then demonstrate, before any event, to the satisfaction of our society, that we have done all we ought to, to ensure safety? In general, this will be by demonstrating due diligence in our safety decisions and action, as required by the model Work Health and Safety legislation. But how is due diligence defined?Lawyers, when asked to describe the nature of due diligence, focus on compliance with legislation, regulations and relevant codes of practice, that is, the law. Engineers, when asked if compliance with acts, regulations and codes guarantees that anything is ‘safe’ in reality, reply “no, of course not. Don’t be silly”.This means there is a substantial practicable gap between ‘legal’ and ‘engineered’ due diligence. The reason is that it is not possible for the laws of man (in the form of regulations and compliance) to predict the future. Our legal system (the courts, Royal Commissions and the like) is hindsight driven, applying the underlying principles of moral philosophy like, "do unto others as you would have done to you.”Due diligence engineering takes these moral principles as outlined by laws and court decisions taken in hindsight, and projects them to future human endeavour. This means that engineering due diligence is about the right thing to do, and not just covering your backside.

This article first appeared on Sourceable.

The Law and Engineering

The notion of engineering due diligence has expanded into Australian society, gradually displacing pure risk management as the ultimate aim of engineering decision-making. Numerous national and state-based laws have moved from mandating risk assessments to imposing specific duties to exercise due diligence, in health and safety, environmental protection and other areas.However, some standards and other non-mandated guidelines, regardless of legislated and common law precaution-based (SFAIRP) requirements and judgments (the laws of man), still promulgate approaches requiring the ‘scientific’ (ALARP) measurement and comparison of risk. This is presumably done with the view that risk can be examined and dissected as part of the laws of nature. Engineering and legal practitioners find themselves caught between these competing paradigms.An egalitarian society like Australia desires to ensure fairness amongst its citizens. One outcome of this view is that no one should be inequitably exposed to risk, and certainly not for the benefit of others. Being a free society, an individual can choose to be ‘riskier’, but this should be a matter of personal choice, not economic necessity.Risk equity can be demonstrated in two key ways. One is a scientific exercise that sets and complies with a maximum level of risk to which any person may be exposed. This requires detailed modelling of potential event sequences and comparison to a predetermined maximum acceptable level of risk.The second provides a minimum level of precaution (i.e. protection from risk) for all persons exposed to the undesired outcomes. This minimum level is generally demonstrated in recognised good practice, i.e. precautions considered reasonable by virtue of their implementation in similar situations.Pre-event, both methods conceptually provide for equal risk outcomes. However, post-event, only the minimum precaution equity approach can be tested objectively – either the precaution was in place or it was not. The maximum risk level equity approach is problematic to justify on a number of levels.The courts, reflecting Australia’s societal desire for fairness, established the precautionary approach in the common law duty of care. Post-event, the courts test whether all reasonable steps were taken to avoid damage to people. This long-established approach considers both precautionary risk equity and financial efficiency in determining what precautions, for any particular event, were reasonable.Unlike the courts, engineers and lawyers don’t have the benefit of hindsight in determining what is reasonable. Decisions must be made, with business, safety, societal and environmental implications, to address any number of potential events. These often include complex issues with valid but irresolvable competing stakeholder points of view.Due diligence engineering expands the courts’ ‘equal minimum level of precaution’ principle to a pre-event precaution-based decision-making philosophy incorporating the requirements of both science (the laws of nature) and society (the laws of man). This philosophy allows engineers and lawyers to together cut the Gordian knot that has developed when decision-making at the complex interface of physical and social infrastructure.

Engineering’s Golden Rule

The Golden Rule, or the rule of reciprocity, states that one should treat others as one would wish to be treated. It is an astonishingly widespread maxim, appearing in some form in virtually every major religion and belief system.As a result, the Golden Rule permeates Australian society, in our courts and parliaments, and our laws and judgments. It is an integral and inalienable part of our social infrastructure.Cambridge professor David Howarth’s recent book, Law as Engineering: Thinking About What Lawyers Do, considers some of the implications of this. Howarth’s thesis is that most UK lawyers do not argue in court. Rather, on behalf of their clients, they design and implement, through contracts, laws, deeds, wills, treaties and so forth, small changes to the prevailing social infrastructure.Australian law practice seems to follow a similar pattern, and this is a good and useful thing; without these ongoing small changes to social infrastructure there would be large scale confusion, massive imposition on the court system, and general, often escalating, grumpiness.Engineering serves a similar function. Engineers, on behalf of their clients, design structures and systems that change the material infrastructure of society.This is also a good and useful thing. And, with the history of and potential for significant safety impacts resulting from these physical changes, engineers have over time developed formal design methods to ensure safe outcomes.These methods consider not only the design at hand, but also the wider physical context into which the design will fit. This includes multi-discipline design processes, integrating civil, electrical, mechanical, chemical (and so on) engineering. It also includes consideration of what already exists, and the interfaces that will arise. Road developments will consider their impact on the wider network, as well as nearby rail lines, bike paths, amenities, businesses, residences, utilities, the environment, and so on.Howarth’s book considers this approach to design in the framework of changing social infrastructure. He argues that lawyers, in changing the social infrastructure, ought to consider how these changes may interact with the wider social context to avoid unintended consequences. As an example, he examines the 2009 global financial crisis in which, he argues, many small changes to the social infrastructure resulted in catastrophic negative global impacts.Following formal design processes could have, if not prevented this situation occurring, perhaps at least provided some insight into the potential for its development. But the question arises: how should negative impacts on social infrastructure be identified? In contrast to engineering changes to material infrastructure, social infrastructure changes tend not to have immediate or obvious environmental or health and safety impacts.One option that presents itself is also apparent in good engineering design. Engineers follow the Golden Rule. It is completely embedded in engineering practice, and is supported and reinforced by legislation and judgements. Engineers design to avoid damaging people in a physical sense. Subsequent considerations include environmental harm, economic harm, and so on.A key aspect of this is consideration of who may be affected by infrastructure changes. Proximity is critical here, as well as any voluntary assumption of risk. That is, potential impacts should be considered for all those who may be negatively affected, and who have not elected to put themselves in that position. This is particularly important when others (such as an engineer’s or lawyer’s client) prosper because of such developments.A recent example involving material infrastructure is the Lacrosse tower fire in Melbourne. In this case, a cigarette on a balcony ignited the building’s cladding, with the fire spreading to cladding on 11 floors in a matter of minutes. The cladding was subsequently found to not meet relevant standards, and to be cheaper than compliant cladding.In this case, it appears a design decision was made to use the substandard cladding, presumably with the lower cost as a factor. Although it is certain that the resulting fire scenario was not anticipated as part of this decision, the question remains as to how the use of substandard materials was justified, given the increased safety risk to residents. One wonders if the developers would have made the same choice if they were building accommodation for themselves.In a social infrastructure context, an analogy may be that of sub-prime mortgages being packaged and securitized in the United States, allowing lenders to process home loans without concern for their likelihood of repayment. In this scenario, more consideration perhaps ought to have been given by the lawyers (and their clients) drafting these contracts as to, firstly, how they would interact with the wider context, and, secondly, whether the financial risks presented to the wider community as a result were appropriate. In many respects the potential profits are irrelevant, as they are not shared by those bearing the majority of the risk.The complexities here are manifest. Commercial confidentiality will certainly play a role. No single rule could serve to guide choices when changing social or material infrastructure, and unforeseen, unintended consequences will always arise. But, when considering the ramifications of a decision, a good start might be: how would I feel if this happened to me?

This article first appeared on Sourceable.

2016 The Year in Review

2016 is almost over, and a new year is fast approaching. R2A has had a great year. Below are some highlights we would like to share with you.

In early 2016 we launched the 2016 update of the R2A text, Engineering Due Diligence, at our annual function. This included Richard’s discussion of one of the first prosecutions of an officer of a company under the newly implemented Work Health and Safety legislation.

Shortly after this R2A took on a new business partner, Tim Procter, who returned to R2A after a number of years working in engineering design and consulting. Tim also joined the Engineers Australia College of Leadership and Management Victorian Committee.

And, not to be outdone, in mid 2016 Gaye welcomed the arrival of her second daughter.

Richard, Gaye and Tim are now looking forward to R2A’s next event. On 7 February 2017 R2A and the Victorian Bar will welcome former British MP Professor David Howarth, Reader in Law at Cambridge University, to Engineers Australia’s Melbourne centre. David will discuss his recent book, Law as Engineering, and his thoughts on some interfaces between lawyers and engineers. This will be a larger event than we have previously held – registrations are available through Engineers Australia’s events website. We’re planning that this be the first in a series of seminars exploring this subject. We’d love to see you there.

Interesting Projects

- Transurban: R2A completed a review of all fire safety systems for Transurban’s Australian tunnel portfolio, with a particular focus on what constitutes recognised good practice for aging assets.

- Public Transport Victoria: R2A conducted project due diligence reviews for a number of PTV business cases involving trams, trains, buses, safety and accessibility projects.

- IPART: R2A provided advice to IPART, the NSW electricity safety regulator, on the development of an audit framework for electricity network safety management systems. This was an extensive project that involved reconciling a number of concurrent pieces of legislation to ensure the framework was acceptable to all stakeholders.

- Legal advisory services: R2A advised our clients and their legal counsel in a number of confidential projects relating to the implications of the new WHS legislation for their operations and management.

- Department of Land, Water and Planning: R2A advised DELWP on the implications of the new WHS legislation when considered against the revised Australian National Committee on Large Dams (ANCOLD) guidelines.

- Port of Melbourne Corporations: R2A are undertaking an asset safety due diligence review for a critical piece of Port infrastructure.

Gaye has also been appointed to the Energy Safe Victoria Powerline Bushfire Safety Committee, which will continue its work in 2017.

Conferences

Richard and Tim presented at a number of conferences and seminars in 2016, and are available for similar opportunities in 2017. Please get in touch if you have an event coming up.

- Conference on Railway Excellent (CORE) 2016. Rail Tunnel Fire Safety System Design in a SFAIRP Context. Co-authored by Tim Procter and Lachlan Henderson of Metro Trains Melbourne.

- Asset Management Council and Risk Engineering Society (Melbourne). Risk and Asset Management.

- Dust Explosions Conference, 2016. Dust Explosions and the (Model) WHS Act.

Media

R2A were featured in a number of publications in 2016. The Sourceable articles in particular (listed here chronologically) show our evolving thinking on the implications of the precautionary approach in engineering decision-making and the wider society. This culminated in our final article for the year, which presents our view of the history and philosophy of the ISO/AS31000 (hazard-based) and WHS/common law (precaution-based) approaches to risk management, and the conflicts that have arisen between them.

- Are Australian Standards Becoming Irrelevant? (Sourceable) (No longer available).

- Precaution v Precaution (Sourceable)

- Unknown Knowns: the Perils of Blind Spots (Sourceable)

- Problems and Solutions: The Power of Perspective (Sourceable)

- Legal vs Engineered Due Diligence (Sourceable)

- Everyone is Entitled to Protection – But not Always the Same Level of Risk (Sourceable)

Tim also had a paper published in the 2016 edition of the peer reviewed Australian Journal of Multi-Disciplinary Engineering: Due diligence in the operation and maintenance of heritage assets.

Education

Throughout 2016 Richard delivered public and in-house courses on Engineering Due Diligence to a wide range of attendees.

Richard also continued to present the Swinburne University post-graduate unit Introduction to Risk & Due Diligence. In 2016 this was made a core unit for all engineering post-graduate degrees. Gaye, Tim and R2A associates presented guest lectures during the semester. With this increased enrolment Tim and Gaye will be joining Richard as regular lecturers in 2017.

The 2-day joint R2A/EEA Engineering Due Diligence workshop was again successful this year and will continue in 2017. This workshop is aimed at aspiring directors and senior managers.

Precaution v Precaution

One of the more interesting philosophical issues to emerge in the early 21st century is the relationship, as determined by our courts, between the precautionary principle as implemented in environmental legislation, and the precautionary approach as articulated in the harmonised Work Health and Safety (WHS) legislation.It is interesting because the intellectual source of these ideas appears entirely different, yet the judicial operationalisation of both approaches appears to align.The environmental precautionary principle is generally recognised as coming from Germany’s democratic socialist movement in the 1930s and gained acceptance through the German Green movement in the '70s and '80s as a formal articulation of the German principle of vorsorge-prinzip, that is, quite literally, precaution-principle. In Australia, Parliaments adopted the formulation derived from the Rio convention in the '80s as expressed by the Intergovernmental Agreement on the Environment (1992) between the Commonwealth and the States. That is:"Where there are threats of serious or irreversible environmental damage, lack of full scientific certainty should not be used as a reason for postponing measures to prevent environmental degradation.In the application of the precautionary principle, public and private decisions should be guided by:(i) careful evaluation to avoid, wherever practicable, serious or irreversible damage to the environment; and(ii) an assessment of the risk-weighted consequences of various options."The precautionary approach in the model WHS legislation appears to be derived as a defence against negligence in the common law. The common law (commencing in the 12th century with King Henry II) is now established from case law as modified progressively by the judiciary over the next 800 years and, in particular with regard to negligence, by the English law lord Lord Atkin in 1932. He favoured the adoption of a manifestation of the ethic of reciprocity or the golden rule of most major philosophies and religions, expressed in the Christian tradition, as: love your neighbour as yourself meaning do unto others as you would have done unto you.In The precautionary principle, the coast and Temwood Holdings, published in the Environmental and Planning Law Journal 2014, Justice Stephen Estcourt summarises the attempts by the judiciary in Australia to operationalise the environmental precautionary principle over the last 20 years and describes the way various decisions depend on earlier decisions and the way in which aspects of possibly unrelated decisions can be ‘borrowed’ (for want of a better term) from other judgments. For example, he observes that Osborn J in Environment East Gippsland vs VicForests (2010) notes the Shirt calculus. Wyong Shire Council v Shirt (1980) considers the liability of the Council for a water skiing accident, which at first glance would not appear to have any obvious connection to an environmental forestry matter. The issue was a question as to on which side of a sign saying ‘deep water,’ the water was actually deep.What the judges appear to be doing is extracting what are perceived relevant principles from other decisions. This has been conceptually noted by others. In their book Understanding the Model Work Health and Safety Act, Barry Sherriff and Michael Tooma quote a decision from the NSW Land and Environment Court to establish what due diligence means in the model Work Health and Safety legislation. Their point is that, whilst due diligence has been defined in the model WHS Act, the definition closely mirrors the current definition of due diligence in case law. That is, existing environmental case law may serve as a guide to this interpretation for WHS legislation.From the perspective of due diligence engineers trying to reverse engineer the decisions of the Courts, all this is actually quite refreshing. Deconstructing the precautionary principle back to established common law protocols to establish due diligence facilitates a robust pre-event alignment of the laws of nature with the laws of man.

This article first appeared on Sourceable.

Mixed Messages from Governments on Poles and Wires

According to the Australian Energy Regulator (AER), unexpected events that lead to substantial overspend by owners of poles and wires is capped to 30 per cent.

The rest can be transferred through to the consumer. That is, it does not have to be budgeted for.

Quoting the AER:

"Where an unexpected event leads to an overspend of the capex amount approved in this determination as part of total revenue, a service provider will be only required to bear 30% of this cost if the expenditure is found to be prudent and efficient. For these reasons, in the event that the approved total revenue underestimates the total capex required, we do not consider that this should lead to undue safety or reliability issues."

This has the immediate effect of making poles and wires a valuable saleable asset as the full cost of risk associated with large, rare events like the 2009 Black Saturday bushfires in Victoria does not need to be included in the valuation. For example, the recent, cumulative $1 billion payout in Victoria has relatively little effect on the profit outcomes for the owner. It also means that the commercial incentive to test for further reasonably practicable precautions to address such events is greatly reduced.

This is inconsistent with accepted probity and governance principles. Ordinarily, all persons (natural or otherwise) are required to be responsible and accountable for their own negligence. At least this is the policy position adopted by responsible organisations like Engineers Australia. Their position requires members to practice within their area of competence and have appropriate professional indemnity insurances to protect their clients. The point is that owners and operators should be accountable for negligence, which the commercial imperative desires to abrogate.

In the case of the Black Saturday bush fires for example, this governance failure has been practically addressed by our customary backstop, the legal system, in the form of the common law claims made by affected parties, and the outcomes of the Bushfire Royal Commission and the flow on work by the Powerline Bushfire Safety Taskforce and the continuing Powerline Bushfire Safety Program.

Particularly, the use of Rapid Earth Fault Current Limiting (REFCL) devices (aka Petersen coils or Ground Fault Neutralisers) on 22-kilovolt lines has been demonstrated to have very significant ability to prevent bushfire starts from single phase grounding faults, faults which the Royal Commission found to be responsible for a significant number of the devastating black Saturday fires. A program to install these in rural Victoria at a preliminary cost of around $500 million appears inevitable, but under the current regulatory regime this cost will be (mostly) passed to the consumer. It is a sad reflection that it takes the death of 173 people to get the worth of such precautions tested and established as being reasonable.

Our Parliaments have seemingly addressed this in a convoluted manner by implementing the model Work Health and Safety laws in all jurisdictions (presently excepting Victoria and Western Australia). This makes officers (directors et al) personally liable for systemic organisational safety recklessness (cases where the officers knew or made or let hazardous occurrences happen) providing for up to five years jail and $600,000 in personal fines. In Queensland, it’s also a criminal matter. There have not been any test cases to date so the effectiveness of this legislation has not been evaluated.

From an engineering perspective, the exclusion of the cost implications of big rare events from the valuation of assets means irrational decisions with regards to the safe operation will inevitably occur and that the community will periodically suffer as a result.

This article first appeared on Sourceable.

Engineers Australia Safety Case Guidelines Due to Be Released

The Engineers Australia Safety Case Guideline (3rd Edition) is presently being reviewed by Engineers Australia legal counsel.

It is expected to be released by the Risk Engineering Society through Engineers Australia Media in early 2014.

This third edition of the Safety Case Guideline considers how a safety case argument can be used as a tool to positively demonstrate safety due diligence consistent with the model Work Health and Safety (WHS) legislation (Work Safe Australia 2011) and the Rail Safety National law amongst others, and to provide general information concerning the concepts and applications of risk theory to safety case arguments.

The Guideline adopts a precautionary approach to demonstrating safety due diligence, meaning that safety risk should be eliminated or reduced so far as is reasonably practicable (SFAIRP) rather than reducing risk to as low as is reasonably practicable (ALARP) as encouraged by numerous Australian and international standards and regularly used by many Australian engineers. The Guideline emphasises that attempting to equate SFAIRP and ALARP is naively courageous and will not survive post-event judicial scrutiny.

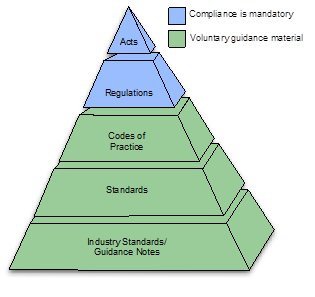

The expected adoption of the Guideline represents the intellectual tipping point in the technical management of safety risk, at least in Australia, since a guideline or code of practice published by practitioners in their area of competence takes legal precedence over an industry-based standard unless that standard is called-up by statute or regulation. The call-up of a standard in legislation is frowned upon by parliamentary counsel since it derogates the power of parliament to unelected standards committees rather defeating the purpose of a parliamentary democracy. Advice is that under the new safety legislation the hierarchy is now:

In a discussion of the legal status of standards, Minter Ellison partner Paul Wentworth concluded that "Engineers should remember that in the eyes of the courts, in the absence of any legislative or contractual requirement, an Australian Standard amounts only to an expert opinion about usual or recommended practice. Also, that in the performance of any design, reliance on an Australian Standard does not relieve an engineer from the duty to exercise his or her own skill and expertise."

Previously, due diligence meant compliance with the laws of man. The Guideline emphasises that to be safe in reality (meaning an absence of harm), one must first manage the laws of nature rather than the laws of man. Safety due diligence therefore requires a positive demonstration of the alignment of the laws of nature with the laws of man, in that order.

This is quite different to demonstrating due diligence in the finance world. Money isn’t real. That is, it does not exist in a state of nature, for example, it does not grow on trees and therefore the laws of nature don’t directly apply to it. This means that in the financial world, due diligence will probably continue to be considered the same as compliance. Equating due diligence with compliance is an approach many audit committees pursue with regard to safety risk but which is now effectively prohibited by statute law in most Australian jurisdictions.

This article first appeared on Sourceable (no longer available).

Sustainability Due Diligence

Australian parliaments – supported by decisions of the High Court – have been encouraging the adoption of due diligence as a general concept to be applied throughout Australian society.

For example, due diligence in legislation is now called up by the Corporations Act (Cth) legislation, environmental legislation (e.g. NSW and Vic), model WHS legislation and Rail Safety National law etc.

In addition, earlier decisions of the High Court have been endorsed the idea. For example, the judges of the High Court unanimously agreed with the NSW Court of Appeal in 1980 [1] that due diligence as called up in the Hague Rules (to which Australia is a signatory) meant due care against negligence.

Due diligence is a legal concept. It represents an aspect of moral philosophy, that is, how the world ought to be and how humanity should behave in order to bring this about.

In practice, it seems to be an implementation of the ethic of reciprocity, often referred to as the Golden Rule in most philosophies and religions. Essentially, this means treat others as you would expect to be treated by them, or, do unto others as you would have done unto you. At least, that is what Lord Atkin indicated in Donaghue vs Stevenson (1932) [2].

In court this seems to be often tested (with the benefit of hindsight) in the form of the reasonable man test, meaning what would a reasonable man have done in the same circumstances. This is a complex idea as an American law professor notes [3]:

"The reasonable person is not any particular person or an average person… The reasonable person looks before he leaps, never pets a strange dog, waits for the airplane to come to a complete stop at the gate before unbuckling his seatbelt, and otherwise engages in the type of cautious conduct that annoys the rest of us… “This excellent but odious character stands like a monument in our courts of justice, vainly appealing to his fellow citizens to order their lives after his own example."

Much of all this is summarised in the Engineers Australia Safety Case Guideline (3rd edition), which is being launched at the National Convention in Melbourne this month. But what does all this mean and where are we heading, at least as engineers?

As something of an intellectual exercise, an attempt to apply the anticipated requirements (the logical consequence set) of recent Australian legislation and the common law decisions to date as they might be applied to global warming was presented last month by the authors at the NSW Regional Engineers Sustainability conference in Wollongong [4].

Our courts and parliaments require that, when it comes to the examination of human harm post event, all reasonable practicable precautions are demonstrated as being in place at the time decisions were made. To achieve this requires a number of steps.

The key steps for a due diligence argument are:

- A completeness argument as to why all key plausible critical issues were identified

- Identification of all physically possible precautions for each plausible critical issue

- Identification of which precautions in the circumstances are reasonable, balancing the significance of the risk vs. the effort required to achieve it (cost, difficulty and inconvenience and whatever other conflicting responsibilities the defendant may have).

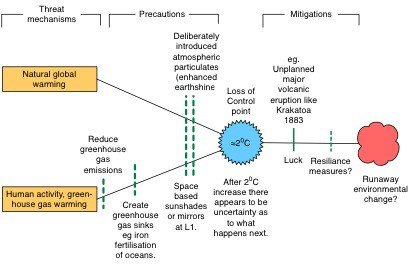

Based on CSIRO studies, it does seem that the planet is warming. Whether this is entirely due to human activity (greenhouse gas emissions) or natural forces is argued extensively, but there does seem to be general agreement that for the 6 billion people on planet Earth, more than two degrees Celsius is problematic. After that, no one’s too sure what might come next. A runaway temperature change that melts the three-kilometre deep Greenland ice sheet [5], for example, will result in a seven metre increase in sea levels, with dire consequences for low lying seaboard cities like Melbourne. This certainly seems a plausible, critical scenario and one that Australian governments should be seen to consider carefully.

Many options are being discussed to address the issue, including controlling carbon emissions, which has proved politically difficult and - if the planet is naturally warming - ineffective. A recent remarkable claim by Lockheed Martin’s “Skunkworks” that fusion energy is only five years [6] away would certainly address this.

There are, however, a number of other, apparently viable precautions of differing costs and effectiveness. The Krakatoa explosion [7] of 1883 apparently cooled the planet by about 1.2o degrees Celsius for a year as a result of the increased albedo effect (reflecting sunlight back in to space). We don’t yet seem to be able to predict such events in advance, so cooling the planet by that means would seem to more a matter of good luck than good governance.

Such precautions can be summarised in a threat-barrier diagram (TBD):

Central to a TBD is the loss of control (LoC) point. This is the point at which the laws of nature and man align. Legally, precautions act before the LoC whilst mitigations act after it.

There are a number of possible options available that would achieve a similar effect to a Krakatoa 1883 explosion, including pumping moisture into the air [8] to produce more reflective white clouds.

Sun shields such as the La Grangian L1 point between the Earth and the sun [9] would be effective too. Another method, possibly the cheapest and most effective of the lot, seems to be the fertilisation of the Southern Ocean [10] to create carbon absorbing algal blooms which would both cool the planet and act as a carbon sink, thereby de-acidifying the oceans.

According to Treasury [11], the Victorian desalination plant has presently cost the Victorian taxpayer $5.7 billion despite the fact that no water has been purchased. The reason for the plant's construction seems to based on a due diligence argument.

At the time of the decision, much of Australia had experienced a 10-year drought. If this had continued for another 10 years, the possibility of a major Australian population centre running out of water was deemed quite plausible. As state cabinet had the means within its power to ensure that this could not happen, it was done, even if it more likely than not will never be needed.

$5.7 billion is a lot of money. Many of the ideas mentioned to address global warming apparently could be implemented for such a sum. If so, it would appear to be within the power of the Victorian parliament and society to prevent a plausible catastrophic flooding of Melbourne due to runaway global warming.

Provided the science and numbers are right (and it is crucial that this be verified and validated), a perpetuation of the due diligence approach would seem to require the Victorian parliament to investigate and potentially act to protect Melbourne – and incidentally cool the whole planet.

References:

[1] Shipping Corporation of India Ltd. v. Gamlen Chemical Co. A/Asia. Pty. Ltd. [1980] HCA 51; (1980) 147 CLR 142

[2] See http://www.bailii.org/uk/cases/UKHL/1932/100.html viewed 17 July 2013

[3] J M Feinman (2010). Law 101. Everything You Need to Know About American Law. Oxford University Press. Page 159

[4] See http://www.engineersaustralia.org.au/events/nsw-regional-convention-sustainable-regional-engineering

[5] http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Greenland_ice_sheet viewed 7nov14

[6] http://www.theaustralian.com.au/news/health-science/lockheed-martin-unveils-miniature-nuclear-fusion-power-generator/story-e6frg8y6-1227092587574?nk=4536f2c5e9e39c3c7dd336b0aae01f5c viewed 7nov14

[7] See http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/1883_eruption_of_Krakatoa viewed 7nov14.

[8] See http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:SPICE_TESTBED_-_DEPLOYED_POSITION.jpg#filehistory viewed 7nov14, for an example.

[9] http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Space_sunshade viewed 7nov14.

[10] http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ocean_fertilization and http://www.acecrc.org.au/Research/Ocean%20Fertilisation and http://marineecology.wcp.muohio.edu/climate_projects_04/productivity/web/ironfert.html viewed 3nov14

[11] http://www.dtf.vic.gov.au/Infrastructure-Delivery/Public-private-partnerships/Projects/Victorian-Desalination-Plant viewed 3nov14.

This article first appeared on Sourceable.

Tough Times Ahead for the Construction Sector?

The Construction Risk Management Summit organised by Expotrade was held in Melbourne on April 1 and 2, playing host to a diverse range of speakers and messages.

Possibly the most common message from academic speakers at the Construction Risk Management Summit was that the majority of projects do not come in on time or budget. In fact, many suffered from a major cost blowouts rate of nearly 100 per cent, with a wide array of reasons blamed for this issue.

The single biggest factor, which was identified by the majority of speakers, was failures in relation to upfront design. Typically, 80 per cent of the project cost is established at this phase. As a consequence, if errors occur during this phase of the project, additional expenses becomes a necessary, often quality controlled outcome. The solution to this issue was to have designers to focus on the long term operational performance, say at least 10 years operation, rather than just on practical completion.

This had several flow-on implications which were expanded upon by subsequent speakers. Knowing who the stakeholders are is critical. Stakeholders need to be understood and perhaps ranked in different ways, for example, as decision makers, interested parties and neighbours, lobby groups or as just acting in the public interest. This requires a culture of listening, which is an area the construction business should be encouraged to address.

Other speakers noted that the culture of the construction business could be changed, with safety in design identified as one cultural change that had occurred in recent times.

It was also noted that competitive pressures are still on the increase in the industry. Lowest tender bidding meant that corporate survival required "taking a chance" on contingencies in relation to risks that one could only hope would never eventuate.

If the construction market continues to shrink, more and more tenderers will be bidding for fewer and fewer jobs, with the final result being greater collective risk taking, or even an increasing likelihood of unethical behaviour.

This article first appeared on Sourceable. (No longer available)

Precautionary Principle vs Precautionary Approach: What's the Difference?

One of the more interesting philosophical issues arising from the introduction of the model WHS legislation is the question of whether the precautionary principle incorporated in environmental legislation is congruent with the precautionary approach of the model WHS legislation.The precautionary principle is typically articulated as: If there are threats of serious or irreversible environmental damage, lack of full scientific certainty should not be used as a reason for postponing measures to prevent environmental degradation[1], with due diligence being recognised as a defence in the Victorian Act (Section 66B).The words in Australian legislation are derived from the 1992 Rio Declaration. This formulation is usually recognised as being ultimately derived from the 1980s German environmental policy. The origin of the principle is generally ascribed to the German notion of Vorsorgeprinzip, literally, the principle of foresight and planning[2].The WHS legislation adopts a precautionary approach. It basically requires that all possible practicable precautions for a particular safety issue be identified, and then those that are considered reasonable in the circumstances are to be adopted. In a very real sense is develops the principle of reciprocity as articulated by Lord Atkin[3] in Donoghue vs Stevenson following the Christian articulation, quote: The rule that you are to love your neighbour becomes in law you must not injure your neighbour; and the lawyer's question "Who is my neighbour?" receives a restricted reply. You must take reasonable care to avoid acts or omissions which you can reasonably foresee would be likely to injure your neighbor. Interestingly, in describing what constitutes a due diligence defence under the WHS act, Barry Sherriff and Michael Tooma[4] favourably quote a case from the Land and Environment Court in NSW, suggesting that due diligence as a defence under WHS law parallels due diligence as a defence under environmental legislation.Does this mean that the two precautionary approaches, despite having quite divergent developmental paths have converged?Tentatively, the answer seems to be ‘Yes’. The common element appears to be the concern with uncertainty stemming from the potential limitations of scientific knowledge to describe comprehensively and predict accurately threats to human safety, and the environment.What does this mean? At the least is means that due diligence as a defence against things that can go wrong in Australia is on the up and up.

[1] Victorian Environment Protection Act 1970. No. 8056 of 1970 Version incorporating amendments as at 1 September 2007. Version No. 161.[2] Jacqueline Peel (2005). The Precautionary Principle in Practice. Environmental Decision Making and Scientific Uncertainty. The Federation Press.[3] Donoghue v. Stevenson (1932). See http://www.bailii.org/uk/cases/UKHL/1932/100.html[4] Barry Sherriff and Michael Tooma (2010). Understanding the Model Work Health and Safety Act. See p 43. State Pollution Control Commission v RV Kelly (1991).